Discover the Story

J. William Middendorf II was prepared for tough decisions and leadership early in his career. He was a naval officer in World War II stationed in China, first as a member of the occupation forces and briefly as part of the security for General George Marshall, who tried to broker peace between Mao Zedong and Chiang Kai-shek. Marshall halted the shipment of weapons to the Nationalists in 1945, a decision that placed the Communists in control of China four years later. Like many of the officers who made up the occupation team, Middendorf was horrified when a writer for the New York Times described Mao Zedong as the “George Washington of Asia.”

As a businessman in Cuba in 1958, Middendorf was among the first to identify Fidel Castro as a devoted Communist with direct connections to the Soviet Union. At the same time, American journalists were praising Castro for bringing freedom, free elections, and prosperity to Cuba. Middendorf escaped Havana in a small plane with bullet holes in the fuselage, placed by Castro’s machine guns.

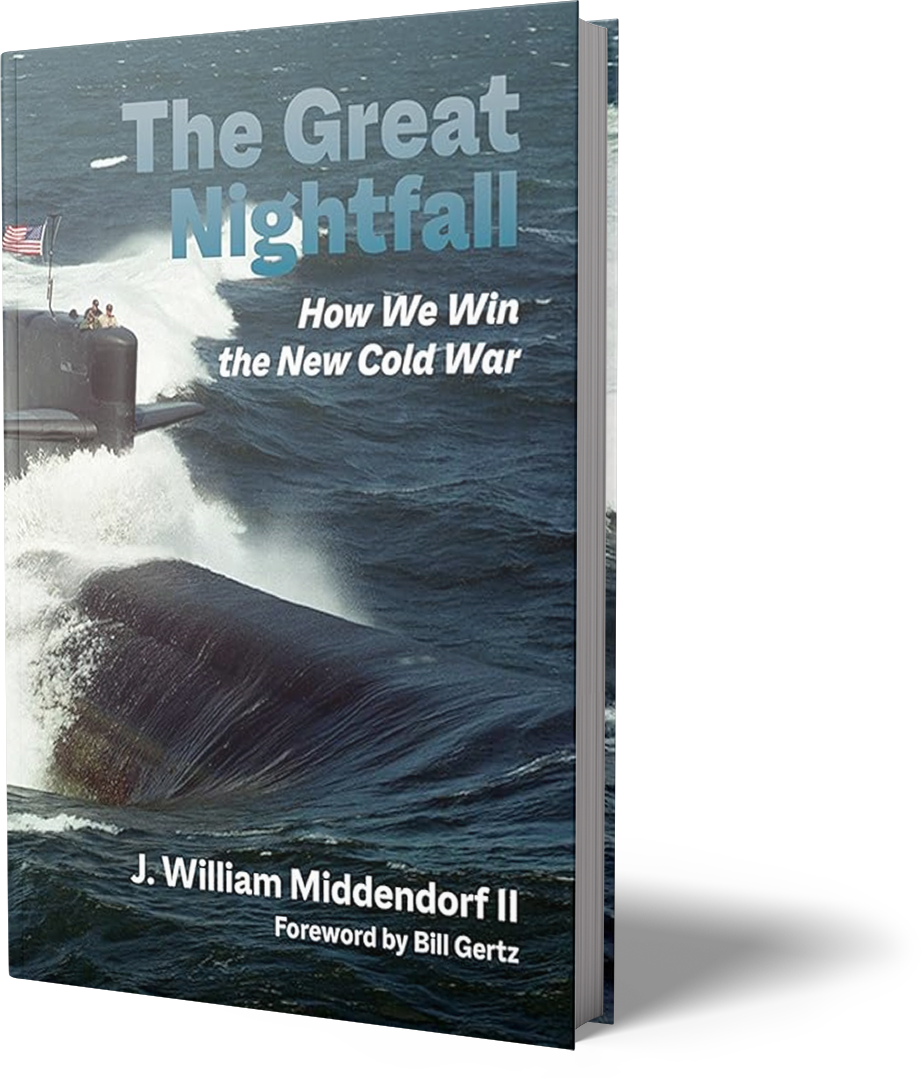

At 40, Middendorf founded a company with a seat on the New York Stock Exchange. He could have settled for business success, but he decided instead to pursue a career in public service. Making money was important, but making a difference was more meaningful to him. In 1969, he left his investment firm and accepted the role of U.S. Ambassador to The Netherlands. He became Secretary of the Navy in 1974 when the Soviet Navy threatened to overtake the United States naval power. Middendorf worked to maintain America’s competitive edge under presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. He supported the development of vital programs, most notably the Trident missile for Ohio-class submarines, the Aegis missile defense system with its 80 Arleigh-Burke class cruisers, and the F/A-18 combat jet.

In April 1975, President Ford reached out to Middendorf to devise a plan to evacuate thousands of Americans and at-risk Vietnamese from Saigon as the Viet Cong took over the country. Admiral Holloway and Middendorf came up with “Operation Frequent Wind,” in which helicopters took Americans and friendly Vietnamese to ships of the Seventh Fleet in the South China Sea. For 18 hours, 81 overloaded and crammed helicopters piloted by exhausted men ferried 1,373 Americans and 5,595 Vietnamese and third-country nationals to freedom.

As Secretary of the Navy, Middendorf had a good relationship with Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran. Middendorf’s warnings about Ayatollah Khomeini and the revolutionaries attempting to overthrow the Shah were ignored, creating a dangerous foe for the United States. Iran’s abrupt transformation from a reliable U.S. security partner and hub for American investment to an anti-American regime led by an ascetic cleric confounded Washington.

In 1980, President-elect Reagan assigned Middendorf as the interim head of a transition team for the CIA. His team recommended a policy requiring information sharing between the CIA and the FBI. It also urged more stringent internal security because the Soviet Union was executing many of our spies behind the Iron Curtain. The CIA rejected all of the recommendations from Middendorf’s team. If the information-sharing policy had been adopted, 9/11 might have been averted. All 19 of the terrorists involved in 9/11 were on a CIA watch list when they landed in this country for pilot training. The list was not shared with the FBI. Increased internal security might have prevented Aldrich Ames, head of the CIA’s Counterterrorism group, from selling the names of dozens of our agents in the Soviet Union. Tighter controls might have uncovered turncoat FBI agent Robert Hanssen, the most dangerous spy in FBI history.

Middendorf continued to advance national security as Ambassador to the Organization of American States, where he resisted the expansion of Soviet and Cuban influence in Latin America. One of his first challenges was dealing with the Falklands War that began in April 1982 when the Argentine Military Junta invaded the islands and captured 1,000 British citizens. Middendorf had to walk a tightrope, supporting Margaret Thatcher’s decision to retake the Falkland Islands without offending the pro-Argentine members of the OAS.

One year into his tour as Ambassador to the OAS, Middendorf sounded the alarm on a new runway that was being built in Granada. The small island country was under the command of Maurice Bishop, a communist who had signed trade and military agreements with Havana and Moscow. Middendorf and National Security Council staffer Constantine Menges devised a plan that led to the invasion of Grenada and the restoration of a democratic government.

Middendorf was a tireless advocate for economic freedom in Latin America and was an intellectual force behind the North American Free Trade Agreement. As Ambassador to the OAS, Middendorf was asked about Hugo Chavez and his promises to restore freedom and economic equality to Venezuela. He urged his colleagues at the OAS and his friends in Venezuela not to support the Socialist-Marxist system Chavez proposed, including income inequality, wealth redistribution, and the other usual communist slogans with so much initial traction. His warnings were ignored, as they had been in China and Cuba, where he had first-hand knowledge of the communist threat. Venezuela went from the wealthiest Latin country to the poorest, with a 93% poverty rate. Its humanitarian crisis has resulted in Latin America’s worst refugee and migration exodus.

Bill Middendorf stood at the Berlin Wall in 1991, shortly after President Reagan’s speech urging that the wall be taken down. That same year, as communism collapsed in the Soviet Union, President Boris Yeltsin invited a team from the Heritage Foundation to help draft a constitution for the new Russia. Bill Middendorf was part of the team. Yelstin realized that privatization, the process of transferring state-owned facilities to private sector owners, was the only way the new Russia could survive. After many visits, the Heritage team wrote the Russian Privatization Handbook, which benefited hundreds of thousands of previous state-owned small businesses. However, several critical industries such as coal, steel, and oil were turned over to a group of Oligarchs who now drain huge profits and are directly under Putin’s control. Economic collapse and inflation soon followed. Some of the recommendations made by the Heritage team remain in the Russian Constitution today. One spells out an election policy that contributed to the loss of multiple seats in Putin’s ruling party in a September 2019 election.

A delegate to presidential nominating conventions as far back as Barry Goldwater in 1964, Middendorf remains active in shaping conservative foreign, defense, and economic policy through regular meetings with staff members on Capitol Hill. His decision-making, relationship-building, and statesmanship on the international stage have enhanced America’s security and stability during a volatile period in our history. Throughout his brilliant career, he has been devoted to his family and pursued lifelong art and music interests. He has also been a proud member of The Heritage Foundation Board of Trustees since 1989. He served as Ambassador to the Organization of the American States, dealing with the Falklands War and the invasion of Grenada. His last diplomatic assignment was as Ambassador to the European Community, in which he served until 1987.

On Dec. 18, 2023, a keel unveiling ceremony for the USS J. William Middendorf, DDG-138, an Arleigh Burke-class destroyer, was held at the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro said the new ship would be a fitting tribute since Secretary Middendorf championed the Aegis system featured in these destroyers in 1976.

In addition to his career in public service, Secretary Middendorf is a widely respected philanthropist, author, artist, and composer. He wrote the “J. William Middendorf March” in honor of his new ship, played by the Navy band at the ceremony. Composing music and creating art brought joy and balance to his life. He sketched many of the world leaders he met over the years.